Effective Sample Size

Published on 25 January 2025

The more data points you have demonstrating a statistical relationship, the more certain you can be that this relationship exists. In an ideal world with a perfectly random sample, the uncertainty in your estimates will fall as your sample size increases. However, the formulas you learn in stats 101 assume that these data points are independent and uncorrelated.

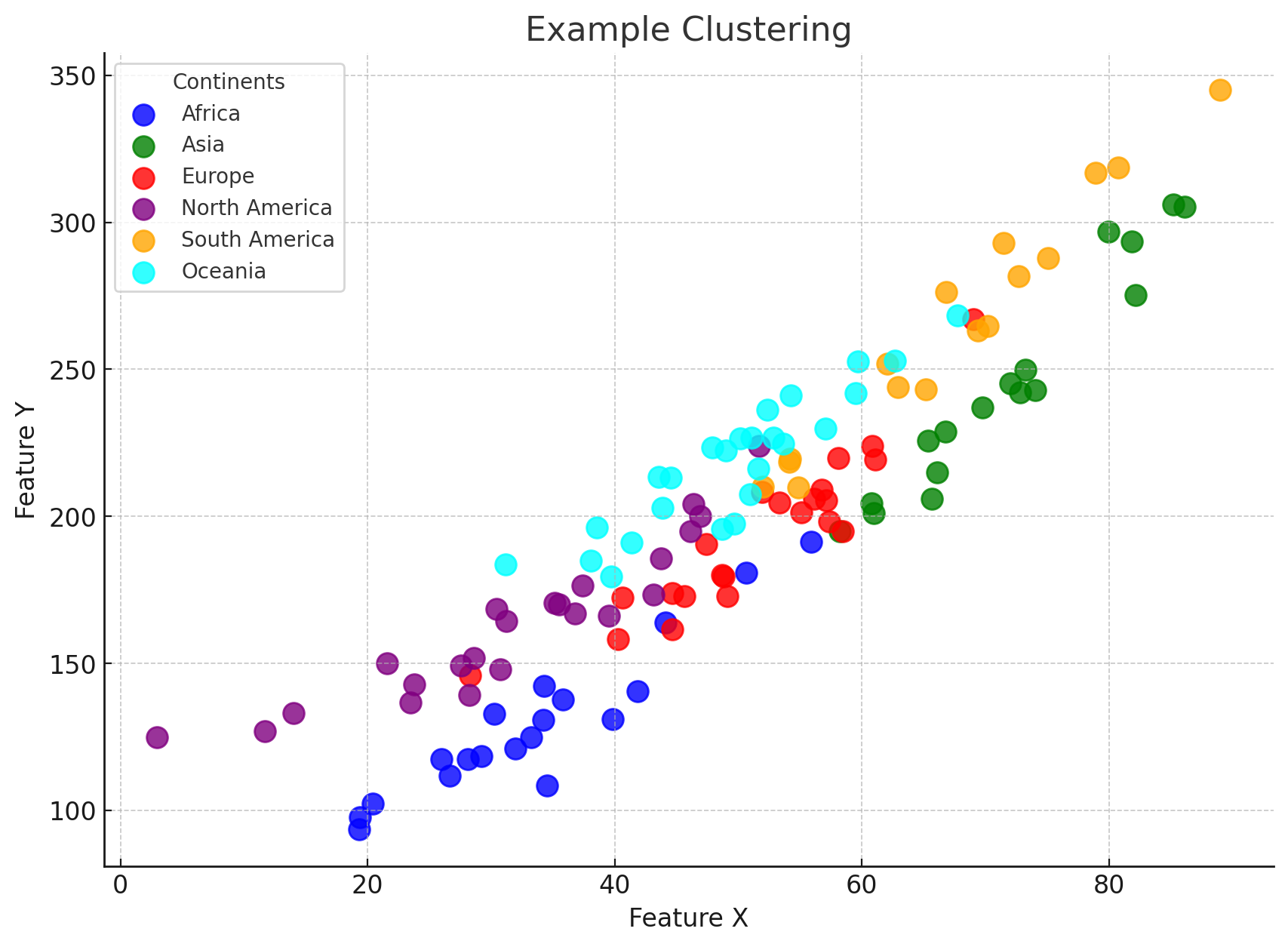

In the above chart, you can see the points, which represent countries, are not independent, because there’s some degree of clustering by continent. So while the sample size might be 122, using that figure will make us far too confident about our model. Alternatively we could just average everything out by continent so that the chart only has 6 data points. This does solve the problem (our points are now independent) but that approach is far too conservative in that our original 122 point-sample provides us with more information than the mere 6 observations at the continent-level.

This is where the notion of ‘effective sample size’ comes in, which adjusts the sample-size to take into account the correlation. The effective sample size for the above example will be less than 122, and more than 6. The more important continent is, the closer the effective sample size will be to 6.

The reason I introduce this notion is that I think it can be useful in other domains. Suppose an organisation hires 100 experts to inform them about a problem. In principle it would generally not make a lot of sense for anyone to contest their conclusions, even if someone else is also an expert what’s the likelihood they know better than the 100 employed experts?

Or to give a concrete example: I know nothing about immunology, but by May 2020 I was reasonably confident that any vaccine for covid would have issues with antigenic escape, as coronaviruses tend to evolve rather rapidly and evidence suggested covid was no exception. The authorities insisted however that the vaccine would provide herd-immunity until late 2021 when direct evidence to the contrary became overwhelming. Why was I so confident? Partly it’s because public health bodies are highly politicised, but even in the absence of that I would take their assertions with a grain of salt. The principal reason is because, in my experience, group-think runs so high in most organisations that the effective sample size of experts who contributed to their statements can be counted on one hand.

In other words, if you tell me that all the experts in a discipline at the top universities believe in x, that might be thousands of people. But I’ll likely interpret the effective sample size of experts as maybe 8. In other words, if you got more than 8 independently-minded smart people to look at the evidence and vote on it, I’d trust their conclusion above that of the thousands of university professors. The professors’ opinions are so highly-correlated due to various mechanisms (e.g. hiring for faculty being done on ideological lines), that each individual adds essentially no confidence to their conclusions.

To give another example of this phenomenon, say you ask the man on the street what makes a good election poll, they’ll probably say ‘accuracy’, i.e. how likely is it to be close to the final election result. But ask Nate Silver, and you’ll get a very different response. One way pollsters try to boost their own accuracy is by herding, by looking at similar polls and fudging their own numbers so it looks more like everyone else’s. This makes sense, any individual poll has sampling variance, if your poll is an outlier it is genuinely is more likely to be wrong than everyone else’s is wrong.

The issue for Nate Silver is that he has a model which looks at all the polls, so when you add a herded poll into that ensemble it really doesn’t improve the confidence of the model. Conversely a non-herded poll, one which might be notoriously inaccurate for other reasons, will still do more to improve Nate Silver’s model than an accurate highly-herded one. Indeed, a perfectly herded poll (i.e. one which doesn’t even use their own numbers at all), adds no new information whatsoever, it increases the effective sample size of the polls by 0.

So by way of analogy, supposing you’re hiring for an organisation and you want your organisation to be most correct about something so you can beat your competitors. Most hiring managers would naively assume the best way to improve organisational correctness would be to hire the most correct individuals, but that’s almost the opposite of what you want to do. The best way for an individual to reduce their own error is often just to defer to mainstream opinion. But once you’ve hired one guy like that, there’s no point hiring any more, you’re not improving organisational accuracy you’re just hiring more guys with identical opinions which will give you an unjustified confidence in your organisation’s predictions, in much the same way adding in herded polls does nothing for Nate Silver’s model.

What you want to do is hire people who are often right and independently-minded, keeping in mind that independently-minded people might on average be more wrong than group-thinkers. Then you can try to come up with various processes which allow these people to resolve their disagreement (e.g. debate) and some sort of process to reach a conclusion when people don’t reach a consensus (e.g. voting). Naturally, you might also want to select for people who are good at disagreeing as well.

I don’t think anywhere really does this, indeed bureaucracies typically want to minimize internal disagreement, so behave in almost the exact opposite manner. They actively prefer group-thinkers. Once you further consider other reasons they tend to be wrong (e.g. capture by vested interests), I dare say that the average government body is less trustworthy than a single disinterested smart person.

An interesting question then arises with regards to AI. ChatGPT is already pretty good at telling you the single most mainstream answer to any given question. In theory this makes group-thinkers even more redundant, you can just use ChatGPT if you want the most authoritative answer for a given question. But I suspect the more likely outcome is that ChatGPT will, over time, be seen as infallible, making it even harder for independently-minded thinkers to get by. If we get ASI this doesn’t matter, but I wouldn’t be surprised if we have a long period where AI can’t make genuinely novel breakthroughs while, at the same time, the people who can do are discriminated against all their lives for occasionally disagreeing with AI, which will be considered the mark of a lunatic.