Google vs Government

Published on 15 March 2025

I work in a dysfunctional area of government and I’ve always been struck that a single private firm appears to share all of the same organisational pathologies: Google. It’s not immediately obvious why this is; Google is still a young company by absolute standards and works in an industry far removed from the public sector, however there are some structural similarities which I believe explain the resemblance.

Firstly, some context about where I work. We’re constantly restructured, during these restructures there’s often a lot of replacement and radical restructuring of middle-management, while lower-management and their teams simply get moved about in the org chart (or between departments) This is partly due to union rules but there are other causes not worth going into.

This means middle-managers have short job tenure. They have little time to accumulate institutional knowledge and networks, and less incentive to build them up (because they won’t be around long to benefit from it). As I mentioned in an earlier essay, they’re also just underpowered, unable to control much discretionary budget or make major personnel decisions.

The result is power resides in the lower-level teams and their managers, which must be largely functionally independent of other teams/areas because at any moment they might be ripped from their home and placed somewhere else entirely (including in another department). Naturally the result is that where I work is highly decentralised.

The same is true of Google, which was famously built on a decentralised model, sometimes known as ‘loosely coupled, tightly aligned’. The idea was that by having largely autonomous product teams it would allow individual product teams to innovate and take risks without endangering the company as a whole. This also meant different approaches and technology for building software could be trialled at a team level, and then the lessons learnt be applied elsewhere if were proved effective, something much more difficult to do if there’s a single ‘best-practice’ everyone must always abide by. Now early on this worked fairly well, but like government there are natural centralising tendencies always at work, which is best explained via a digression.

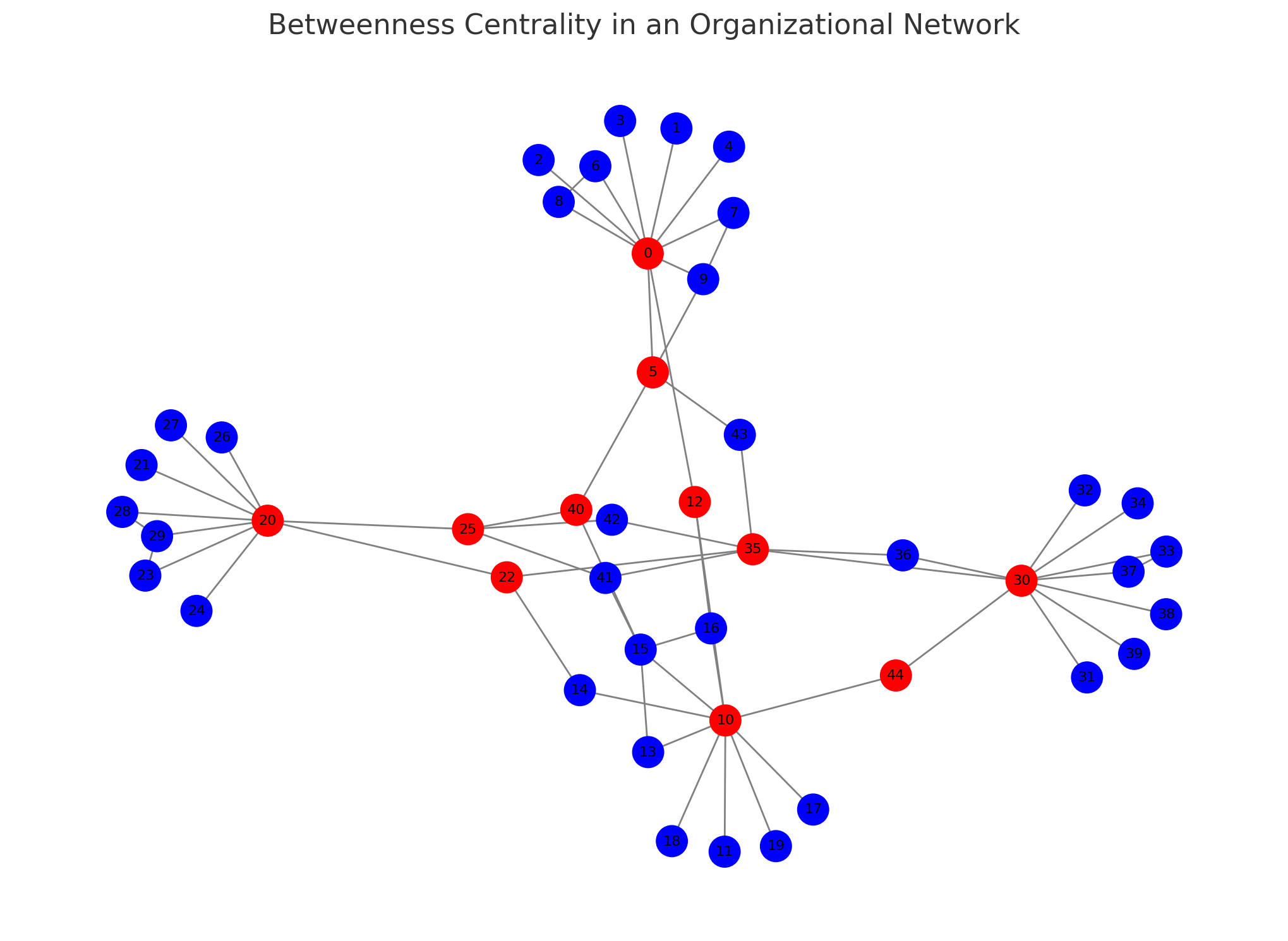

In organisational network theory, it’s a standard claim that nodes (i.e. teams, individuals, whatever) with a high degree of betweenness-centrality wield more social power. Knowing lots of people is great, but it’s even better if they don’t know each other so you can act as a conduit of information between them, potentially play them off against one another, or form coalitions which no-one else is placed to do. As the number of connections might be limited by time (you can’t know everyone at a company), a viable strategy is to try to maximise betweenness-centrality per connection (like the red nodes below).

Note that the power of management often partly rests on their high centrality. We tend to envision an org chart as pointing up or down, so that the y axis maps to pay/seniority. But another way to organise the data would be to have the CEO in the centre of a circular map of dependencies. This brings to focus the basic fact that if two random nodes on a map want to coordinate, the shortest path will often be through management. This in turns allows management to regulate information flows between different areas of the organisation and so forth.

Or to give another example, imagine an unpopular dictator. Whence does his power derive? It might be the case that the top general has more power in the military, the head of secret police has more authority there, the top judges over the judiciary etc. But if the dictator is the central node which connects these various elements together then he’ll quite naturally end up a lot of power, he only has to worry about conspiracies which allow networks around him to form that circumvent him.

While managers might not understand the theory, it’s pretty obvious on the ground that a team or area which manages to sink its tendrils in every other part of the business is going to be better-positioned to accumulate more power over time. I have no idea how it went down at Google but hypothetically we can imagine a scenario like this:

A product goes down for many hours damaging brand reputation etc. Some site reliability engineers go to senior management and say “if you want to prevent this happening in future, we need to ensure all teams conform to best practice, not allow this wild-west approach where each team does its own thing. Even if each team were theoretically able to maintain their own highly-capable SREs, it’s such a niche speciality that we’d be paying far too much in terms of duplication.” Senior management agrees so now SRE gets to be a cross-cutting team which now regulates all the product areas. They build tools, or checklists, or whatever and then force the teams to comply. This is the source of ‘compliance culture’; it’s not something particular to government, if you’ve accidentally recreated the structure of a government organisation in a private firm you’ll observe the same behaviour.

Of course I use SRE just as an example, but there are plenty more are likely to end up spanning the org chart, both technical teams (cybersecurity, infra, QA, devops), but especially administrative teams like HR tend to fall into this category as well. All these areas end up over-powered because they have higher betweenness-centrality than the product areas.

This main ramification is that accountability and incentives are broken. The original structure worked very simply: the head of a product area was responsible for that product being successful and had sufficient power and autonomy to deliver. This fulfills an important principle of good governance, that power and accountability need to go together.

Now instead you might have a security team whose sole responsibility is security. However there’s typically a trade-off between security and other concerns, a trade-off that the security team is not in a position to make, being only responsible for one side of the equation. In government it’s common for it to be virtually illegal to be able to use a computer - this is what happens when security policy is set by a security team who have no interest whatsoever in allowing things to be built. They can effectively ruin projects in the happy knowledge that it’s someone else’s problem. So this is the principal recipe for the dysfunction you see in government and Google:

- Compliance teams, who in theory are there to provide auxiliary support, are far more powerful than the people who do the core work (e.g. that generates revenue for the business), because they have higher network centrality.

- These compliance teams have every incentive to be red-tape maxing, as the downsides of red-tape are an externality for them.

- Product teams are not in a good position to push back. If infra says ‘you have to do x, senior management signed off on this, every other team is doing x’, it’s very hard to say no. Especially if you’ve not been allowed to hire your own infra guys because it’s supposed to be managed organisation-wide.

It’s extremely important to understand that this is downstream of organisational structure. For instance, the founders of Google were very intent on creating an ‘engineering culture’. However even by the late teens it was widely noted that engineers had far less power than HR. The issue here is Google’s founders tried to endow their company with a culture which was not maintainable in the long-run due to structural decisions made early-on. So long as engineers were siloed in product teams, while HR spanned the organisation, then HR will always win in the long-run. Google in its original state was very far from a stable equilibrium, there was a mismatch with its structure and its culture, which is why the culture changed so quickly and so dramatically even compared to other big tech companies.

If, conversely, Google had been built in a centralised unitary fashion from the get-go, I’m sure the founders would have successfully ensured that engineering was more powerful than HR. This is why a decentralised organisation which becomes more centralised over time will typically be much more dysfunctional than one which was centralised from the beginning; the latter would have been designed from the ground up in a sensible fashion.

Finally, it’s worth considering the final state of such an organisation. Because I assure it’s not ‘security is really tight, infra is really good’, etc. Rather to get any work done whatsoever core delivery teams have to start lying to try to circumvent the insane amounts of red-tape. For instance whenever I do any work I call it a ‘proof-of-concept’ simply to avoid having to go through years of approvals processes. So in practice things still devolve into a wild-west, but now there’s also a lot of lying and politics involved.

Because the core teams don’t actually comply with all the insane rules they’re meant to, they stop even trying to push back when ‘best practice’ becomes even more absurdly impractical. So you get a radical divergence in ‘best practice’ which is supposedly being instituted according to the paperwork, and what’s happening on the ground. The regulatory teams are fine with this outcome as when something goes wrong they can claim they were misled by the product teams who lied in all their compliance paperwork, so there’s very little pressure to actually enforce the red-tape, only to make it and pretend it’s being followed.

I don’t think the problem is necessarily all that difficult to solve. For instance you could have it that policies which affect product teams are decided by committees dominated by representatives of the product teams. Alas very few managers seem much interested in organisational theory, they’d rather talk about ‘culture’ rather than recognise the culture is invariably downstream of concrete decisions management has made.